Sensory Awareness

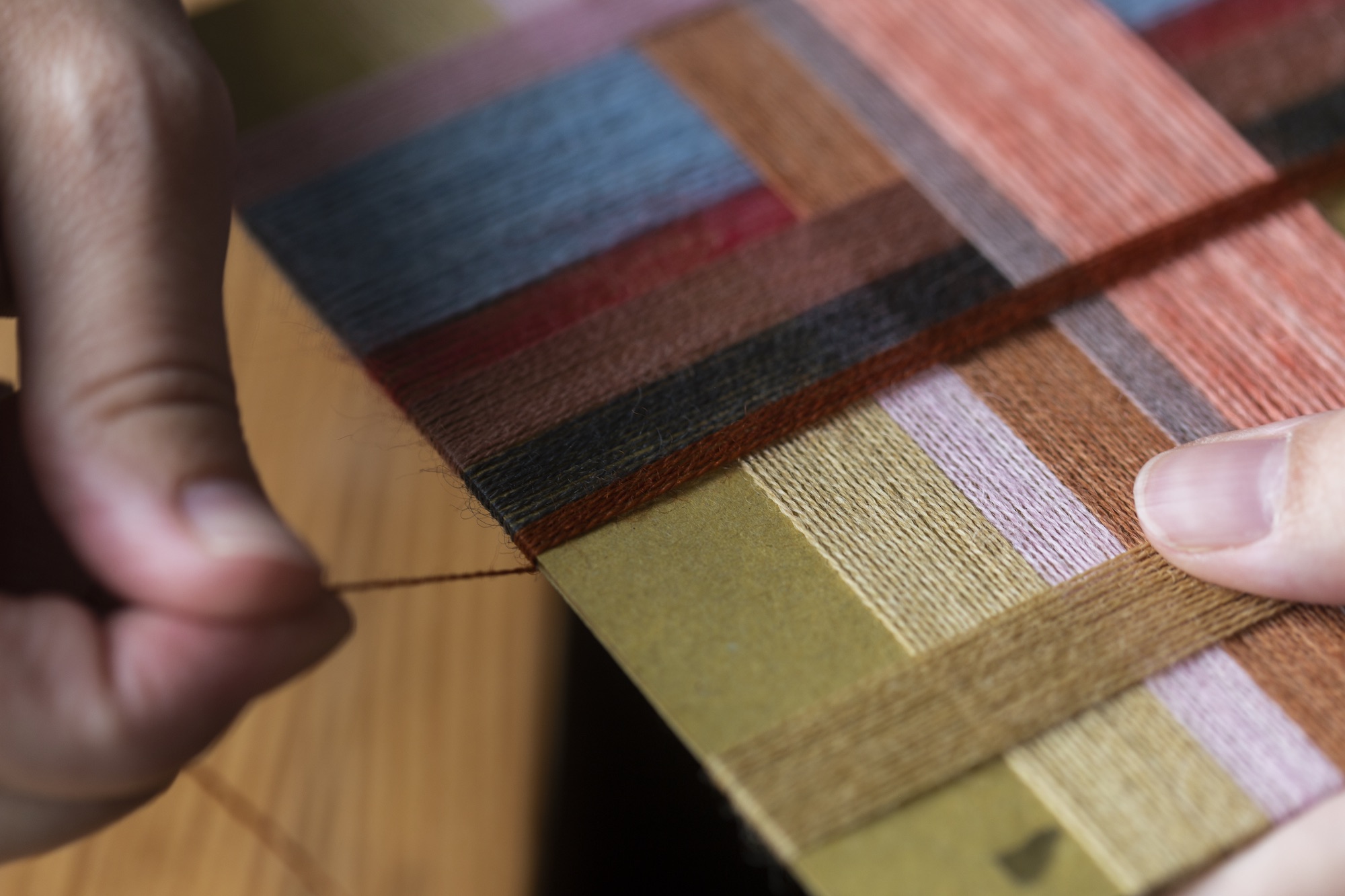

Process in the studio in Aarhus. Photo: Iben West

ASTRID SKIBSTED

… graduated in textile design from Design School Kolding, 2010. Since completing her studies, Astrid Skibsted has had her own studio and practice, which is split between artistic projects and dissemination. Her artistic practice takes as its starting point weaving and the commercial decorating opportunities in that field, such as the liturgical robes for Saint Nikolai’s Church in Kolding. Or the yarn windings, which have grown more and more influential over the past 10 years, creating an artistic and scholarly foundation for development. Astrid Skibsted lives and works in Aarhus.

Textile designer, weaver and artist Astrid Skibsted has made yarn winding an art form in itself and a piece of art in its own right. Here too, yarn winding is also a communication tool between body and mind, between thread, possibilities and details. This introductory text I wrote for her book “The Yarnwinding Manifest”.

“We’ll sit in here,” Astrid says, leading me to a room snugly outfitted with a loom, knitting machine, and shelves of yarn. Here, in a nook in the heart of Jutland’s largest city, lies her workshop, which she shares with a colleague. Whatever the workshop lacks in square meters, it makes up for in the view. The panoramic view of Aarhus’ harbour is unsurpassed anywhere else on this sunny morning.

Astrid has me wrapped up for the morning. Physically. We will create yarn windings together, she and I. It’s important, she asserts, to understand how the principle works and feel it in your own body. I’m in. Completely in, and looking forward to getting my fingers in the yarn, and all its colour and structure. Different yarns are laid out. Large industrial cones and smaller samples, balls, and remnants. Colourful, subdued, and discreet. Coarse, rough, fine, shiny, gleaming, smooth, and matte. A world of possibilities. We get started. Each of us chooses a piece of cardboard in a base colour and then the first strand, which we attach on the back with a piece of tape. We wind the thread around the cardboard. Three times, four. Tape on the back side. We swap. Choose the next thread. Which colour works together with the one Astrid chose as her first? And do I wind alongside Astrid’s thread or across it? Hmm…

Yarn Winding Art. Photo: Suzanne Reitzma

Sharing a yarn winding turns you into co-creators of each other’s works and broadens your own understanding of the constellation of colour, structure, pattern, and composition. Oh, is that how you’re doing it? Are you wrapping tightly or loosely? With dense or diffuse stripes, where there is distance between the threads? Astrid and I continue winding, trading, selecting thread, winding, trading, selecting—and talking, once in a while. Mostly about yarn winding and the potential in what’s happening. Because what is it, in the end, that is happening? What is it that happens when people wind together? We talk freely, because we haven’t actually agreed that we are having a conversation. We’re together for an activity that, in principle, doesn’t mean we must talk. Perhaps we don’t have anything to talk about. Perhaps we do. The premise for gathering is something else—namely, yarn winding. But conversation bubbles up—involuntarily and borne of something concrete. Practical. Material. And whatever else comes up, while the threads allow themselves to be wound.

Astrid Skibsted in her studio in Aarhus. Photo: Iben West

Winding is a game, an experiment, that doesn’t demand any special qualifications other than cardboard, yarn, tape, and time. Winding is a method to open up your flow, your inspiration, your head—and it’s a state where you shouldn’t plan or think, just be. Winding can be everything or nothing, play or seriousness, colourful or bland, but most of all, it’s meaningful. Meaningful to immerse yourself in the simple routine of choosing a thread and winding it around, horizontally and vertically. In layers. In turns. See it take shape. Assess the interplay of the composition. Experience the light, reflected differently on the threads depending on whether they are matte or glossy, made of flax, wool, or cotton. See how the colours interact with each other and with you. Observe how something so simple can become so complex in just an hour. Feel how peace settles into your system, and how present you are. Here and now. In the work and the winding. With yarn, colour, and surfaces that you know by feel.

There’s something meditative about yarn winding. It’s obvious to everyone who tries it. You create. A playful experiment or a textile work of art, just by winding a thread in two directions. Winding becomes a thing unto itself. A path in the world, built from an intuitive understanding of and fascination with the potential of the colours and the material elements. Yarn windings are about composing without needing to be “neat.” Winding welcomes disruptions to the harmony. A variation in the thread or its complexity. A nuance of hue between two seemingly identical colours. An entire composition of contrasts between colour, thickness, and pattern. A difference in height and depth. An unfiltered understanding of the materials. Winding is a way to get to know the materials. To understand with your eyes and hands how they serve as complements and contrasts to each other. To wind a single thread and slowly discover what exactly that particular thread can do. How it plays off the others. That’s about the thread—and the material in itself.

Astrid Skibsted in her studio in Aarhus. Photo: Iben West

Yarn winding was originally a tool for the weaver, used to feel out how the different threads would behave and interact on the loom. How they would stand in relation to each other. How they would take on colour from their surroundings and become new based on whom they stood next to and how the light reflected off them. Yarn winding is an artistic tool for an artistic process, in which you weave between tradition and innovation. With pacing and presence as the ultimate weaving partners. For you must be willing to be swallowed up, to become part of the rhythm of the weaving and the patient work of slowness. To then win the prize, when you at long last pull the textile from the loom and see whether the threads have behaved according to the planned colour shifts, or whether they have exerted their own autonomy, there amongst themselves.

Astrid Skibsted herself says that she decided on weaving due to her temperament. The preparation of planning the yarn, colours, pattern, of setting up the loom and still not having the full picture until the work is finished—this appeals to her. The act of being in the present moment, together with the thread and the material, comes together with her temperament and character, which has always sought to be immersed in and absorbed by the process of creating universes.

Astrid Skibsted in her studio in Aarhus. Photo: Iben West

Yarn winding has become Astrid Skibsted’s undisputed artistic tool, not only for weaving, but for the creative process, drawing her into the universe of colour and to insights about the winding routines that balance between needlework and art. Drawing her into the rewards of sharing the potential of colour and material to others. The potential of colour is also at play in the new interior design trend where colour is no longer only for walls, but for doors and window frames, something which could previously have been perceived as controversial, or as a sign of poor taste.

Today it’s almost mainstream to paint in the same block colours suggested and endorsed by “influencers”. But is colour exclusively fashion, or can it serve as an extra scholarly dimension alongside form and function? Many have worked seriously and professionally within the field—from former Bauhaus luminaries like Anni and Josef Albers to Denmark’s own iconic Poul Gernes and visionary Verner Panton, to the current and relevant Margrethe Odgaard, who develops colour systems independent of their eventual uses.

Art in stacks. Photo: Suzanne Reitzma

Anni Albers spoke of courage as a vital factor in creativity. Courage and slowness. Conscious, thoughtful experimentation—and she believed that creative innovation always comes from the work of the hand. In her 1952 article “On Weaving”, she writes:

Beginnings are usually more interesting than elaborations and endings. Beginning means exploration, selection, development, a potent vitality not yet limited, not circumscribed by the tried and traditional.… Therefore, I find it intriguing to look at early attempts in history, not for the sake of historical interest, that is, of looking back, but for the sake of looking forward from a point way back in time in order to experience vicariously the exhilaration of accomplishment reached step by step.

In order to move forward, you must stand on a foundation, a base. Know it, explore it, and from that point, dare to leap forward. Toward that which you find interesting, because everything exists in a context of meaning in relation to others. Creation is a force you must embrace, and, as a weaver, you search for that place where lines, form, colour, and texture merge into a greater whole. Where format, function, and aesthetic converse—for better or for worse. It’s the same with yarn winding. Like Albers’ beginnings, which hold infinite possibilities, the winding determines an unmapped land, begun with the first thread. A land full of paths and roads to be examined and explored. Like a language you are learning to speak.

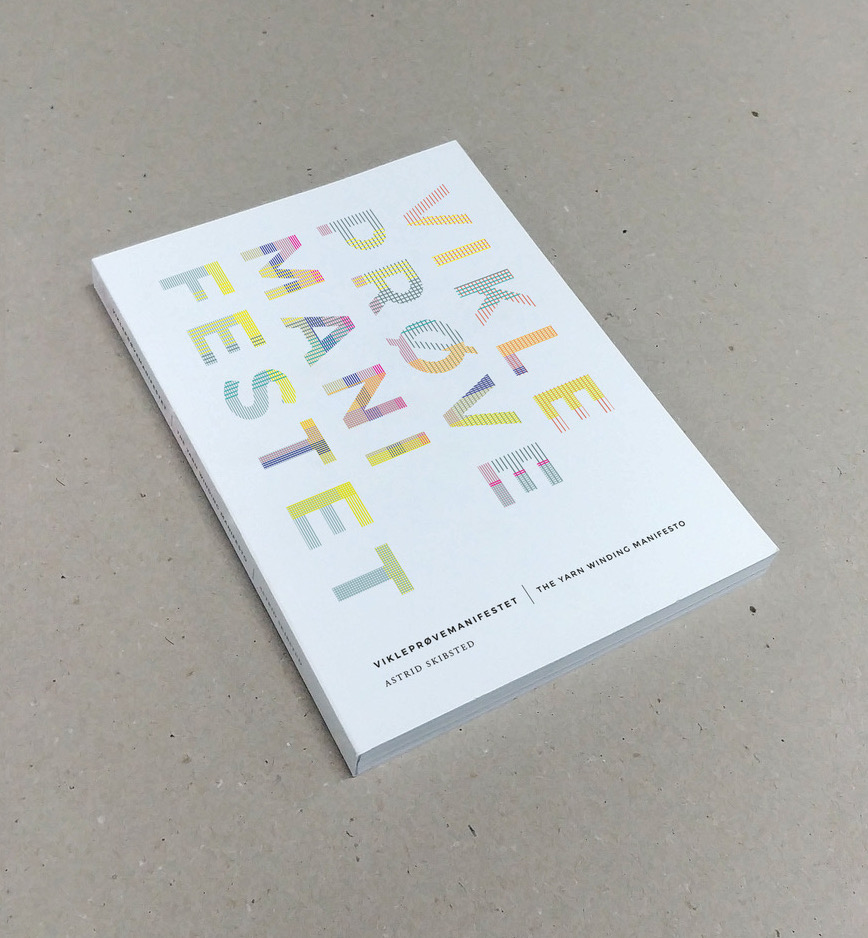

The book ‘The Yarn Winding Manifesto’. Photo: Suzanne Reitzma

Colour is also a language that appeals to the senses. That a colour isn’t just a colour is something most people are gradually coming to realise. But that colours also create peace in the nervous system and release endorphins in the body when you work with them—that’s new and revolutionary. Colours are healing. Poul Gernes showed that, when he set the colour scheme for the waiting rooms and patient rooms at Herlev Hospital and documented that patients stays were shortened when they were in rooms where colour and aesthetic were carefully considered. Verner Panton also worked consciously with colour and psychology, believing that their interaction could cultivate social and cultural transformations.

Colours create an atmosphere that feeds energy or introspection. Most practitioners love both. Disappearing into contagious excitement, and into the aesthetic and functional aspects of a material. Learning something new and transferring that to a creative form. To wind is to create. Endlessly, in principle. Because you can continue. From the sofa, the workshop, together with others. No two are ever the same. Astrid Skibsted has tried, but the works refuse to be identical. They want to be themselves, their own unique expression. In spite of the same format, colour, and yarn. To wind is to lose yourself. And give yourself over to a flow that cultivates a sensory awareness of colour and the world.

—

Inspiration:

Ulrikka Gernes og Peter Michael Hornung: Farvernes medicin, Borgen, 2004

Anni Albers, On Weaving, Early Techniques of Thread Interlacing p. 52, 1965

Ida Engholm & Anders Michelsen, Verner Panton – miljøer, farver, systemer, mønstre, Strandberg Publishing, 2017

ASTRID SKIBSTED

… graduated in textile design from Design School Kolding, 2010. Since completing her studies, Astrid Skibsted has had her own studio and practice, which is split between artistic projects and dissemination. Her artistic practice takes as its starting point weaving and the commercial decorating opportunities in that field, such as the liturgical robes for Saint Nikolai’s Church in Kolding. Or the yarn windings, which have grown more and more influential over the past 10 years, creating an artistic and scholarly foundation for development. Astrid Skibsted lives and works in Aarhus.