Future design symbioses

Future design symbioses

The practical and aesthetic potential of fungal mycelium was illustrated by The Growing Pavilion presented by Biobased Creations and the Dutch Design Foundation at Dutch Design Week 2019. The bio-based rotunda is related to the fungal architecture that the Royal Danish Academy’s professor of bio-hybrid architecture, Phil Ayres, is experimenting with. Press photo.

ANNI NØRSKOV MØRCH

… is a historian of art and ideas with an independent practice as a curator and writer. She has been responsible for exhibitions and research and communication projects at the intersection of art, craft and design. In recent years, she has taken a particular interest in jewellery and its ability to couple intimate and collective aspects. Since January 2022, she has also been the head of the Danish Arts Foundation’s Committee for Crafts and Design Project Funding.

The text is translated by Dorte Herholdt Silver

We have an all-important problem to solve: the sustainability crisis, which is turning the design of additional objects to weigh down the planet into a dubious activity. Do fungi or robots have a lead role to play in future design scenarios?

The sustainability crisis comes with a philosophical quandary: not where to find room for all the design objects but to find the right place for human beings in this dawning world order, where humankind can no longer be seen as the centre of everything – in fact can no longer be preserved as a delimited existential or physical whole. There are worlds within us and around us. We are intimately connected with other entities, from bacteria to plants and planets. Today, design is already manifested in symbiotic partnerships between human being, machine and nature, so how do we envision future design?

The concept of design is historically associated with the Arts and Crafts movement, which a century ago insisted on craft and the human imprint in a new world of industrial mass production. Over time, design became a general term for the intentional process of drawing and developing products, eventually extending into materials and processes, with or without a direct human imprint.

In the Arts and Crafts tradition, the gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art, represented an ideal of the decorative and functional coordination of craft and art disciplines in a single manifestation in which individual components and disciplines formed a coherent whole. As Anders V. Munch writes in a presentation of his dissertation on the gesamtkunstwerk, From Bayreuth to Bauhaus, in the Carlsberg Foundation’s 2013 yearbook, modern design developed as part of society’s ‘total architecture’, shaped by a holistic perspective with goals that go far beyond the form of the individual product.

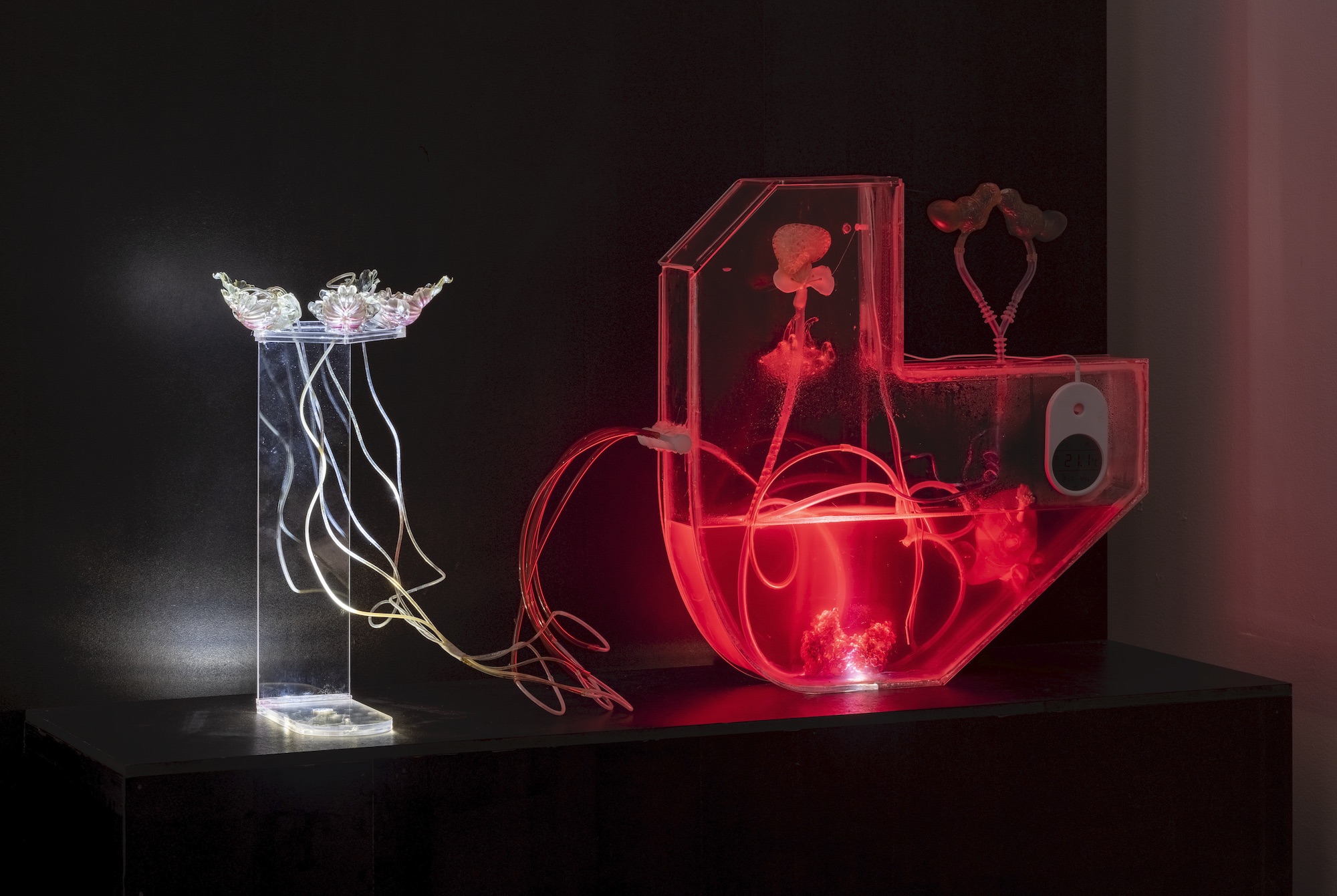

Pinar Yoldas: Copulation-Free Reproductive Organ for Pollution Affected Humans, 2021. Installation view, The World is in You, Medical Museion and Kunsthal Charlottenborg, 2021. Photo: David Stjernholm. Courtesy of the artist.

Gesamtkunstwerk and news value

However, if I were asked right now – on the threshold to 2022, which, even before the first announcements of Covid cancellations of New Year’s concerts, smells as fresh and promising as a day-old dishrag – to point to a contemporary gesamtkunstwerk, I would not turn to the pleasure of works of convincing sensuous harmony or seek satisfaction in sublimely functional design products. What seems to be sprouting and breaking through everywhere, in defiance of the current crisis fatigue, as today’s gesamtkunstwerks are projects that span across science, art and nature with unprecedented radicalism. The boundaries being crossed today are not those separating classic craft disciplines but the boundaries between weaving, architecture and fungal growth; between AI, indoor climate and monolithic mycelia; between flowers and computer science. Human processing – the X-factor that the Arts and Crafts Movement insisted industrial production needed in order to render our industrialized future human, beautiful and meaningful – is no longer regarded as essential.

One of the more exquisite craft and design experiences in 2021 was the exhibition series at the new exhibition venue for ceramic art in Copenhagen Peach Corner. On 30 September, Peach Corner presented News Value, curated by Danish ceramicist and designer Ole Jensen. Throughout his career, Ole Jensen has consistently pursued innovation, always seeking new paths and choosing his own turn when the mainstream path points straight ahead – or pausing and reflecting when others rush forward. As curator, he collected a varied and competent selection of artists for News Value, all focused on a brief that was no small declaration of trust: creating something entirely new. What might a new utilitarian object be? A charged and weighty question today – at once sparking existentialist reflections, requiring innovative thinking and representing Stone Age tangibility. Underneath lurks the question of how we can maintain human existence while safeguarding nature’s, to a reasonable degree, while creating new stuff.

Material experimentalist Jonas Edvard framed and displayed his fungal co-designers in the exhibition News Value at Peach Corner. Photo: Ole Akhøj.

One of the exhibitors was designer and material experimentalist Jonas Edvard, whose work is guided by the motto ‘form follows materials’. He grows fungi and hemp for furniture and boils seaweed and mixes it with chalk to create a material for lampshades. At Peach Corner, he presented his fungal fabric Myx-skin, based on the fungal mycelium, a network of fine white filaments that is usually invisible to the naked eye. In previous projects, Jonas Edvard has used it to make a chair.

In Myx-skin the mycelium is framed and put on display, a presentation that highlighted the beauty of this unusual material, its unwillingness to yield fully and smoothly to the two-dimensional format simultaneously a reminder of its living, self-organizing origin. The most interesting quality of Jonas Edvard’s design practice is his willingness to surrender part of the process to another life form. Rather than simply harvesting and shaping a raw material, he works with fungi, collaborates with it. It is a humbling thought to ponder that your body and mine contain more bacteria and fungi than human cells. In Jonas Edvard’s work, the symbiosis between human being and fungus is not an abstract idea or invisible scientific curiosity but an explicit approach and a sustainable design construction principle.

Luke Jerram: Gaia, 2018. Detail, The World is in You, Medical Museion and Kunsthal Charlottenborg, 2021. Photo: David Stjernholm. Courtesy of the artist.

Everything is connected

Fungi are also thriving in academic halls. When 2021 turns 2022, the Royal Danish Academy in Copenhagen will have a new professorship in bio-hybrid architecture, which couples living organisms with digital and technical components. Architect and Associate Professior Phil Ayres comes into the position from a background in research, including projects such as Flora Robotica, which experiments with cooperation between robots and plants in the creation of spatial structures, and Fungal Architecture, a project aimed at building with and learning from living fungi on monolithic architectural scales.

Human cooperation with fungi and other life forms was also a topic in Medical Museion’s large interdisciplinary exhibition The World is in You at the Copenhagen art centre Kunsthal Charlottenborg in autumn 2021. Based on recent biomedical research, it illustrates how human beings exist in networks of connections from the microscopic to the planetary level. To accomplish the dizzying ambition of showing how our bodies are connected with the world, the curators incorporated art, history, philosophy, politics and heath sciences.

Familiar hierarchies crumble, and enlightened, culture-building human beings are revealed, as semipermeable membranes inhabited by previously disregarded life forms. And once you have caught the scent of this displacement, you can smell the fermented fragrance of the invasion everywhere. Although most of us, including yours truly, have yet to appreciate the full extent of the displacement, I am beginning to notice the growing interest in nature’s couplings around and inside us everywhere: my kefir bottle proclaims that ‘the garden in your tummy should flourish’, the container boldly decorated with an explosion of colourful flowers in the outline of an intestinal system. Our gut deserves attention, as stated in the title of the young German gastroenterologist Giulia Enders’s fascinating popular science book Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body’s Most Underrated Organ about our digestive system and our best friends forever: the bacteria that dwell inside us.

Before her, another German bestseller author, Peter Wohlleben, demonstrated his unique ability to communicate natural science through relatable narratives. While Enders tells the riveting tale of the unseen life inside our gut, Wohlleben writes with equal impact about invisible cooperation and biosemiotics in the beech wood in The Hidden Life of Trees and The Secret Network of Nature. Recently, another important voice has been translated into both Danish and English: In The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture, Emanuele Coccia proposes nothing less than a rethinking of cosmology and the philosophy of nature. Coccia, who studied agriculture and philosophy and is an associate professor at École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (School of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences) in Paris, announces a radical metaphysical shift in which human beings are no longer the existential centre of philosophy, plants are seen as the central life form, and time has come for a new receptiveness towards other creatures in and around human beings.

Anne Tophøj’s experiments with imparting properties of permeability to a traditional handmade ceramic bowl in industrial ceramic filters resulted in her Permeability Test no. 1 in the News Value exhibition at Peach Corner. Photo: Ole Akhøj.

Arts and Crafts version 2.0

From kefir to philosophy, the message is that humanity can no longer simply gaze at our own navel and maintain an ontological distinction between the products of culture and nature. We need to dig deeper – even into the depths of our own gut – in order to understand that being human simultaneously implies being an insignificant grain of sand in the universe, host to a colony of trillions of microbes and the instigator of the Anthropocene – a geological age profoundly shaped by humankind.

At this point, the main focus of our newfound attention of the emotional life of plants, the architectural potential of the mycelium and the gastronomic rediscovery of fermentation is on the search for solutions to current problems, since we are, metaphorically speaking, standing on arable soil, looking for new crops to reap and feed to the coming generations. However, on the horizon we can glimpse the outline of a transformation that is more profound than simply finding new materials to fuel consumption. There is the potential for a new Copernican turn that turns our gaze away from the enlightened, culture-building human centre and towards boundary-transcending connections and networks and an entirely new understanding of design processes in symbiosis with other forms of intelligence.

It is going to be interesting to see the impact of this dissolution or expansion of human boundaries in conjunction with the other sustainability trend, represented by the growing interest in crafts – perhaps we can even speak of Arts and Crafts 2.0, as our buying behaviour is guided by the mantra of fewer but better things with an emphasis on the local and handmade.

One of the great thinkers and practitioners of the Arts and Crafts movement William Morris, famously said, ‘Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful’. Today, this golden rule is echoed by Glenn Adamson, American curator, writer and former director of the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, who in his 2018 book Fewer, Better Things: The Hidden Wisdom of Objects declares himself ‘pro-object’. In a collection of essays that get deep into the weeds on issues of materials and crafts, he explains how the love of objects is not the same as advocating just any object. Adamson convincingly argues that physical know-how ties our society together, as a well-made object is the result of thousands of years of accumulated human experience and that this embedded material intelligence is what enables us to make better decisions about how to inhabit this planet.

Using traditional cabinetmaking techniques, Rasmus Bækkel Fex elevated a simple chipboard to Potato in the News Value exhibition at Peach Corner. Photo: Ole Akhøj.

Sustainable culture and education

Thus, enhancing material intelligence and craftsmanship is not just of interest to the avant-garde elite who drive inspiration and development; it is also an issue of basic sustainable culture and education, enabling all of us to master cooking, repairs and new and old tools and materials and to participate in the conversation about the products of the avant-garde. Material intelligence is rooted in cultural history and learning, as it is in the continuous preservation of traditions that we pass on the often embodied knowledge of tools and materials.

In the future, these traditions need to coexist with radical innovations and a new embrace of non-human life forms, from fungi to robot technology and new paradigms of production that incorporate new expectations of use, reuse and durability. Our clothes need to last longer than a single party or the average seven or eight uses cheap clothes typically see before they are discarded, and perhaps we may also need to accept that other things, like organic apples or fungal architectural constructions, cannot maintain their form for quite as long.

Around the time of the Second World War, the German philosopher and cultural theorist Walter Benjamin evoked his famous image of the angle of history who is being blown backwards into the future, his gaze on the piled-up rubble of the past. In this time of crisis, as art and design make their both hectic and loving attempts at creating something entirely new, they seem to be driven by a refusal to create more old news to be piled up in the slipstream of inevitable forward progression.

Instead, art and design seek to compel the angel to turn his gaze forward in order to see and change the future. Of course, no one can truly see the future, but today, there are many indications that the Anthropocene will also be the post-Anthropocentric era. The need to embrace other life forms and high tech in the name of sustainability is inescapable, and this will hopefully also result in design and craft objects that are both useful and beautiful.

Søren Thygesen presented Kande fra den Antropocæne tidsalder (Jug from the Anthropocene) in the News Value exhibition at Peach Corner. Photo: Ole Akhøj.

ANNI NØRSKOV MØRCH

… is a historian of art and ideas with an independent practice as a curator and writer. She has been responsible for exhibitions and research and communication projects at the intersection of art, craft and design. In recent years, she has taken a particular interest in jewellery and its ability to couple intimate and collective aspects. Since January 2022, she has also been the head of the Danish Arts Foundation’s Committee for Crafts and Design Project Funding.

The text is translated by Dorte Herholdt Silver