Existential Workflow

Existential Workflow

Personal column

Published at Adorno.design

The process is a vital part of the work of all designers, craft artists, and artists. No one just seems to acknowledge it. Because processes are a bit airy. A bit like working for fun. And does it even qualify as real work? This column attempts to provide an insight into what drives practitioners to live on the poverty line. And why official Denmark should take more responsibility when they are still promoting themselves through “Danish Design”.

The process is a practitioner’s most important tool. The place where everything is in play, ideas are tried, and materials and possibilities are tested. As a communicator in the field for 20 years, I believe that process is the most crucial tool in a designer’s toolbox. It is in the process that you talk to and against your material. This is where, through a tactile approach to materials, a stack of calculations, visual sketches, technique, craft skills, craftsmanship, and an experimental approach, you gain deeply meaningful insights. This is where you, as a designer, talk to yourself in your creative process. Here, you try out ideas in form and material. Here, you adjust your expectations and go to and from your idea in concrete form.

Why is the process vital as a designer?

What is it that the process gives back that you cannot figure out in advance?

And why is it essential to know your materials in depth?

The above questions are not only rhetorical but deeply grounded in any designer’s practice. In my many years as a communicator, I have spoken, interviewed, and discussed with a large part of the Danish field of designers, craft artists, and artists. Common to most is a deep understanding of their material and the possibilities that come with it. It takes years to master a craft. It takes years to exhaust the possibilities of a material. And it takes years to let the link between the two create fruitful constellations, whose mission is to improve the established – be it aesthetic, functional, or metaphorical.

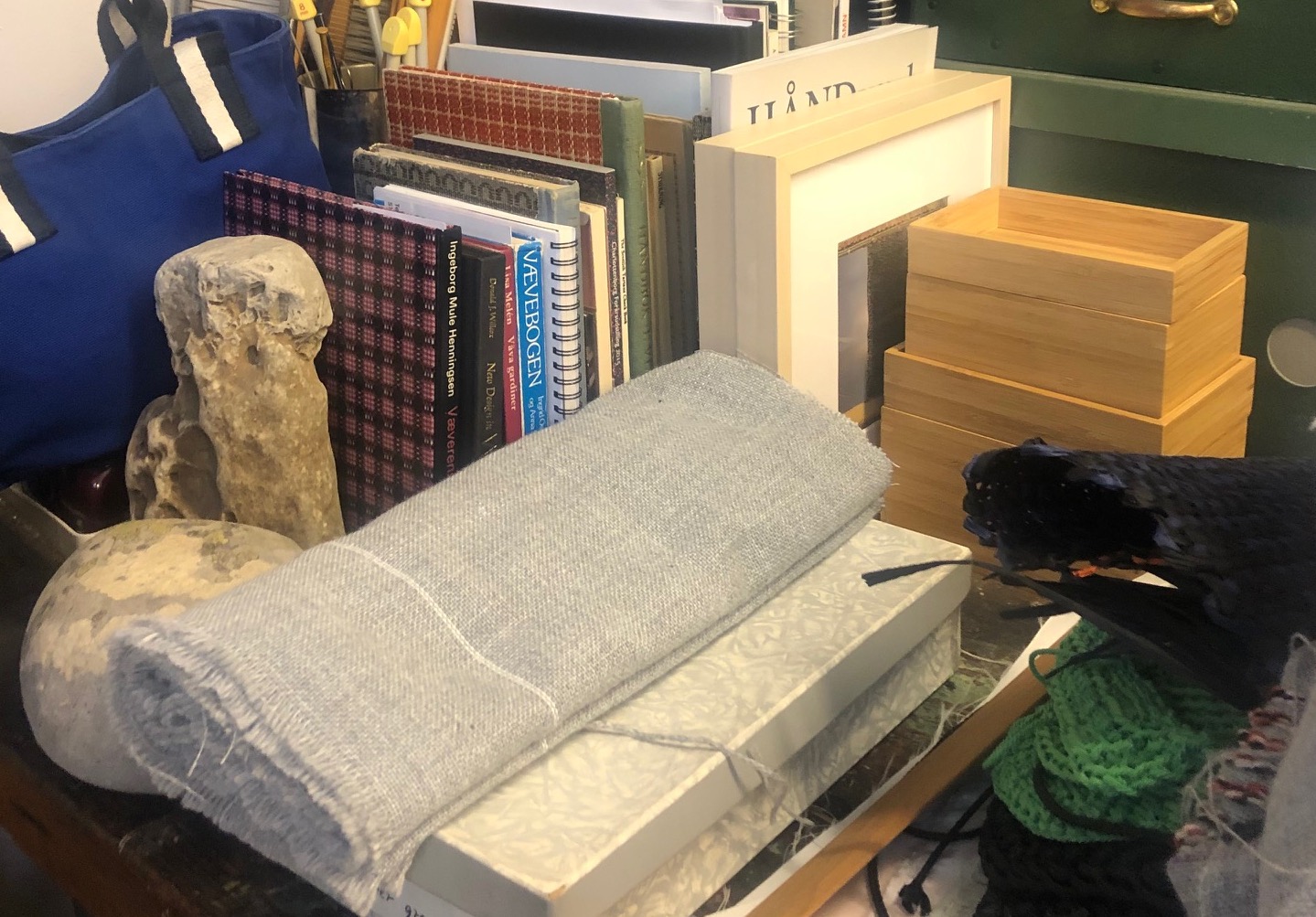

Thora Projects aka Thora Finnsdottirs studio. Foto: Charlotte Jul

In Japan, people like to say that it takes 20 years to learn a craft and 20 years to make it your own. Developing your signature and sharpening your understanding of the material sometimes becomes a practitioner’s physical and intuitive extension. It is also here that you can set yourself free from tradition. Put yourself beyond conventions and reinterpret, turn the original starting point upside down, and bring forward craft – in principle, the whole context around the subject such as expectations, norms, competitors, history, present, references, etc. – to new places.

Most practitioners have an existential approach to their profession. They create from an inner necessity that is synonymous with their personal well-being – and vice versa. To create is often an individual claim that, through the presence and realisation of experience, translate into particular objects, shaped solely because the accumulated knowledge is refined through a long and creative life.

Knowledge of the material, the resistance in it, and its possibilities are a language that the creator has studied for years and excelled in reading, understanding, clarifying, and speaking. Many practitioners have even established their alphabet, which they actively use and refer to throughout their lifelong work. A work, a form, a typology becomes their letters and signature, which they push and develop anew – some for years, others in bursts. That is precisely why creating is a matter of life and death.

Tekstilkunstner og designer Stine Skyttes studio. Foto: Charlotte Jul

There are no quality-conscious artists, craft artists, or designers who create for fun. For the fun of it. Because it’s nice. That premise does not exist. Most craft artists I know have never opened a housing magazine. Not because it does not interest them, but because trends are volatile beings who have no errands in their dwelling. In their practice. In their hands. And they will most likely rather prioritise money for a glaze, the right nut, or heat in their workshop.

When they create, passion, personal agendas, and preferences merge with the material, craft, and history and become a unified whole that triggers meaningful satisfaction. A state of calm, energy, and perfection. When they know the curve is right. When things finally fall into place. When the result is a synthesis of precise idea, material, craft, and aesthetics. In the process of small staging points. In a connected series of large and small experiments, frustrations – and realisations. No realisations, no process. Without process, no realisations. Without process, no pieces.

Thora Projects aka Thora Finnsdottirs studio. Foto: Charlotte Jul

But everything takes time. And diligence. And courage. Ideas, projects, techniques, materials, or collaborations must mature. Take the time they have to take. And be allowed to be at peace in that process. This is why I get annoyed when I experience that designers’ processes and practices are read as a trend that one can adopt, and not a step in a sometimes, extremely sensitive process, where one puts oneself, one’s competencies, and one’s person in insecure fluctuations. Right out there, where it hurts, and there is far to fall.

There is a lack of understanding that a creative workflow is a grave career choice in line with the hard-working and sharp-thinking lawyer. During the Corona crisis’s initial shutdown, it was demonstrated that the vast majority of artists balance or live entirely below the poverty line. Getting paid with a bottle of wine and the joy of working with what they love??? I experience it myself when people think my writing is so good that they reuse it differently without asking for permission or crediting me for it.

Respect for professionalism and wise hands is lacking in our society, where most people buy a copy in the supermarket rather than buying original design and craftsmanship. Because they do not think about it. Because the knowledge society has become our main self-image and global currency instead of wise and competent hands. And knowledge of it. Respect for it. But one does not exclude the other.

Tekstilkunstner og designer Stine Skyttes studio. Foto: Charlotte Jul

Processes occur in all subjects. Not only in the field of design, but this is where they are not fully recognised as vital, necessary, and worthy because only the end result is focused on. Good, not good. Sells doesn’t sell. The process is the designer’s most important tool. To create. To be in the world. Denmark still lives off the “hype” of the great furniture designers of the post-war period, such as Hans Wegner, Børge Mogensen, Poul Kjærholm, Verner Panton, and all the other furniture architects who are relaunched in one go – and enjoy the constant respect that surrounds “Danish Design”.

Many of today’s designers also experience a global interest in Danish design, supported by the successful Danish-global design brands. But I miss more significant support for the field from official Denmark. Such support and prioritisation have not only real economic value but also a substantial symbolic value. Nationally and internationally. It starts with respect for the process. And for the knowledge and pride that lies in wise hands.

Say it out loud:

Wise hands. Wise pieces. Wise practitioners.

A wise country that still lives by its savvy designers…